Room I: Prehistory and Protohistory

Everything we know about the oldest period of our history is due to the remains that have come down to us and through the observation and study of these archaeological remains, thus verifying that Antequera was inhabited by man during the Paleolithic and Neolithic.

The Neolithic revolution brought numerous changes in the lifestyle of our ancestors, moving from a nomadic to a sedentary culture, where houses were created for permanent habitation, developing agriculture and livestock. We find here the first settlers in the Sierra del Torcal during the VI millennium B.C.E.

The contact with peoples from the Near East introduced significant changes, improving their quality of life and activating technological development. The Torcal mountain range was abandoned in search of fertile and flat lands, leading to the proliferation of settlements in the Vega de Antequera. From this stage we preserve remains of almagra pottery, characteristic of the western Andalusian Neolithic.

Later, the use of metals meant a great transformation in the communities of the final Neolithic, where the Campaniform Vase culture was developed. The megalithic culture also stands out from this stage, the first example of monumental architecture, demonstrating that these societies already had a strong religious concept around the cycles of nature. Beyond the architectural aspect of these constructions, such as the dolmens of Menga and Viera and later the Tholos del Romeral, the basic element lies in the mortuary practices that are inseparable from the religious cultural expression.

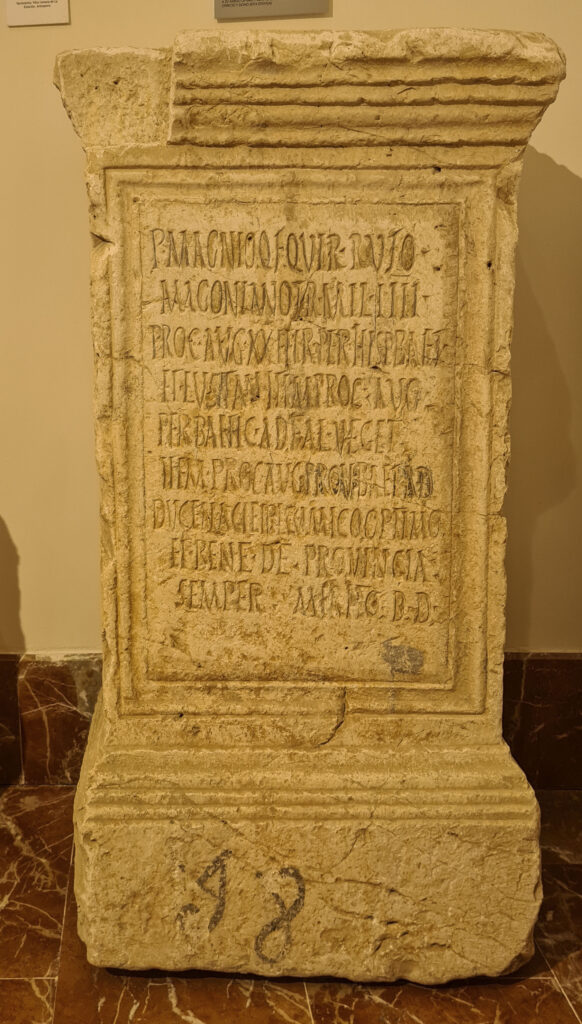

Room II: Epigraphic Collection

These stone bases with epigraphic inscriptions tell us about personalities and relevant facts of the Roman Antequera, which housed the statues to whom they referred, being located in the forum of the city or also in private rooms. Most of these pieces come from the Roman city of Singilia Barba and refer to wealthy local characters. Others refer to the family of the Acilios, whose main benefactor was Acilia Plecusa.

In this space there is also an example of a milestone. This type of column, usually cylindrical in shape, was used as a signpost on roads and streets. They have come down to us thanks to the geographical location of municipalities such as Anticaria or Singilia Barba.

A rare example of a pedestal that housed a statue of the Capitoline She-wolf that was located in the forum of Singilia Barba is worth mentioning. It was as thanks from Marcus Cornelius Primigenius to the Senate of Singilia for the concession of a public place to place the statue of his deceased son. Some copies of capitals of the civil and religious works of the time are also preserved.

Room III. Rome I

The different objects of daily use that this room contains bring us closer to the way of life and customs of the antikariense society, whose presence is documented between the I and V centuries of our era. Objects of toilet, amulets, pieces related to medical practices are some of these elements.

This museum keeps a significant sample of mosaics from different places of the Antequera environment, mainly used for the decoration of interior walls and floors of houses and relevant places of the city formed by numerous glazed tesserae of different colors. It is known that in the Roman Villa of La Estación there was one of the few mosaic workshops in Europe dedicated to the elaboration of mosaics.

The Roman population also showed great interest in the cult and funeral rites either by burial or cremation. Proof of this is the collection of glass as ointments, urns, cups, etc., and the tombs and sarcophagi of incineration. But it is from the third century when the burial as a funerary habit was finally implemented. The monumental mausoleum of Acilia Plecusa is the central and most important piece of this room with one hundred and seventy-three large ashlars. This tomb was conceived to be a family pantheon, although only the skeleton of Acilia Plecusa, an important character in the social life of the city of Singilia Barba, appeared in it.

Finally, the collection of sculptures and pieces made of marble, from the Roman Villa of the Station, Caserío Silverio or Singilia Barba, show us a clear vision of the splendor of the cities and wealth of the luxurious villas during this Roman period. An example, the bust of Nero Germanicus, prince of the imperial family, or the head of Venus, one of the most beautiful of the peninsula.

Room IV: Rome II. Efebo de Antequera (1st century A.D.)

The ephebe of Antequera is one of the most important Roman sculptures of the Iberian Peninsula. Made around the first century AD, in bronze and following the technique of the lost wax, shows a young boy whose aesthetic characteristics and gesture of movement forward his left leg, put in relation to this magnificent sculpture with the classical Greek masters. His eyes must have been made of vitreous paste, holding in his right hand a lampadarium, or bronze lamp. This type of sculptures that adorned the great main dining rooms of the villas, are a sculptural reflection of the young servants who used to attend the banquets.

It was found by chance in the Antequera farmhouse of Las Piletas in 1952 and was declared an Asset of Cultural Interest in 2004 for its historical value and its iconographic variation with respect to other specimens found.

Room V. Roman tomb.

Mosaic of the Erotes, parietal painting and funerary relief.

Room VI. Paleochristian.

In the third century A.D. the population adopted the Christian religion, leaving representations of religious character as paleochristian bricks decorated with the anagram of Christ, called Crismon, or the Greek letters alpha and omega representative of the Christian community in these early centuries and referring to Jesus Christ as the beginning and end of all things. Very interesting is the small bronze sculpture representing the biblical prophet Daniel in the lions’ den.

After the fall of the Empire, the Romanized territories of Hispania were invaded by peoples of barbarian origin: among them the Visigoths, who, in a way, inherited many cultural patterns of the classical world, such as the use of Latin, Roman law and the Christian religion. Due to the scarcity of archaeological sources, the early medieval period of Antequera is little known. However, it has been possible to recover some pieces such as the lintel of a Visigothic church from the 6th century that served as a step in the entrance door of the keep of the Muslim Alcazaba.

Room VII: Medieval-Andalusian-Spanish

The weakness of the Visigothic kingdom meant that, from the beginning of the 8th century, almost the entire Iberian Peninsula was occupied by a new people: the Muslims, who, in the heat of the Islamic religion founded by Mohammed and strengthened by the fury of their warriors, managed to cross the strait to settle in these lands, forging a political and religious entity that during the following centuries would be known as Al Ándalus and under whose influence a new culture would flourish, developing art and commerce.

In the tenth century and under the Caliphate of Cordoba, an urban transformation took place, consolidating the first walled enclosure, the Alcazaba. It was during the Almoravid and Almohad period when the medina was configured, known as Madinat Antaqira in the 12th century. Later it became a strategic and frontier point of containment of Castilian troops, with the reinforcement of the walls and towers and the construction of the barbican.

In the showcases you can see characteristic pieces of the material culture of the Antequera Andalusian period, distinguishing various everyday tools such as a canteen, basins, jugs, cups, candlesticks and ataifores. Among the showcases is located a curious sandstone gargoyle of Nasrid invoice.

Once Antequera was annexed to Castilian lands in 1410, it became a frontier town, becoming a fundamental enclave, developing an important social, economic and population growth. From this period we preserve several pieces that attest to this splendor, such as the chasuble of Santa Eufemia made with Nasrid fabric or the glazed clay baptismal font that belonged to the disappeared parish of El Salvador.

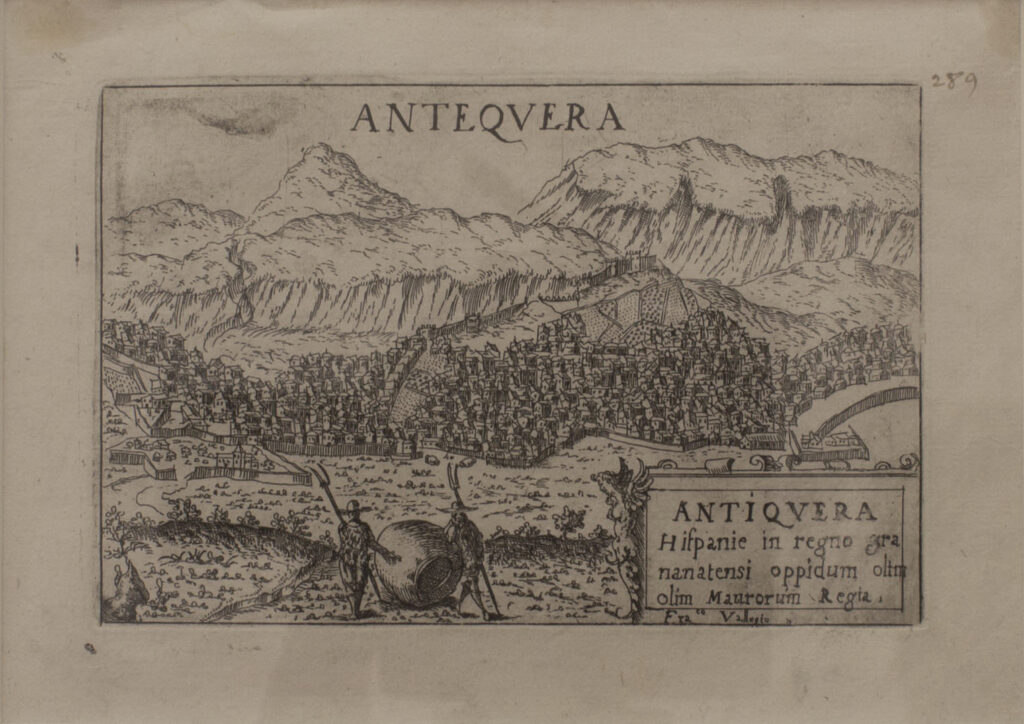

Room VIII: Engravings

This space is dedicated to engravings from different periods related to the history and characters of our city. This collection includes different views of Antequera and some significant enclaves of the city, some of them belonging to outstanding printed works of the time as Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg dated in the sixteenth century. We will also observe a small sample of prints made from photographs or drawings of romantic travelers of the nineteenth century such as Alexandre de Laborde, Louisa Tenison, Lionel Lindsay or Pharamond Blanchard.

Among the illustrious characters we find Francisco Romero Robledo, antequerano who became a minister during the reigns of Amadeo I and Alfonso XII, or General Diego de los Rios who participated in the Carlist wars.

Room IX: The San Francisco of Pedro de Mena

Under a noble Mudejar coffered ceiling, we find two works of Franciscan theme; one, the wonderful work of baroque art belonging to the Granada sculptor Pedro de Mena, the other an oil painting of St. Francis praying of the nineteenth century with some influence of Francisco de Zurbarán.

The sculptural carving made of polychrome wood and dated in the seventeenth century represents the mummy of the saint as Pope Nicholas V found him in his tomb after his pilgrimage to the Patriarchal Basilica of San Francisco. Standing, with the hood of the habit on and looking to heaven, his hands sheathed and showing the stigmata of the crucifixion.

This work, like most of Mena’s works, avoids detail, focusing on pure and fundamental forms, but with an excellent virtuosity in the elaboration of the texture of the habit that increases the volumetric appearance. With hardly any body language, the mysticism of the piece is centered mainly on the face of St. Francis, raising his gaze and showing a restrained passion.

Room X: Mannerism. Transition to Baroque

This room reveals the artistic quality that took place in this city between the mid-sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. This period of cultural, urban, economic and social splendor has left us numerous pieces of great artistic value in a mannerist and baroque style.

We thus contemplate several of the works of Antonio Mohedano, an artist, although mannerist, does not cease to be an authentic precursor of the baroque style. The Marian theme represented here shows an Italianate and eclectic style focused on the volumes of the figure of the Virgin and the naturalism of his compositions.

Other works to be highlighted are undoubtedly the portrait of a lady, of small format, painted by Diego Velázquez, which is part of the Delgado collection, together with the oil painting of Santa Bárbara painted by his slave, Juan de Pareja.

Miguel Domínguez Montelaisla also leaves us a small sample of what was his production in this city and where we observe points in common with the work of Antonio Mohedano, perhaps due to the possibility that there had been a brief artistic relationship between them.

The room is completed with a series of anonymous sculptures of St. Eufemia, patron saint of the city, another of Magdalena penitent belonging to the sculptor Diego de Vega, and an Immaculate Conception of Lorenzo de Medina dated in the sixteenth century that stands out for the Carmelite habit that the Virgin wears.

Room XI: Baroque

This space evidences a whole corpus of images, both sculptural and pictorial, of religious fervor that makes evident the patrimonial wealth and the continuation of the artistic prosperity arisen in previous centuries and whose maximum expression took place in this XVIII century.

These works already belonging to the late baroque have come down to us thanks to the proliferation of artistic workshops in this city and to the sacralization of the daily life impregnated with the religious ideology, very common during this artistic period. The works shown here represent both characters of Antequera’s religious life and works of enormous veneration by this society, such as the Lord of the Greatest Pain, represented here in a painting after the sculptural work of Andrés de Carvajal, greatly revered in the collegiate church of San Sebastián.

This sculptor is the bust of the Virgin of Sorrows, in polychrome wood, which left an important sample of his production in this city.

Room XII: Textiles

Before entering the room and as a background to what is going to be able to visit in this one, you can see a ceiling canopy of pallium made of red damask and gold embroidery, from the eighteenth century. This bambalina is a companion of the one at the entrance of the room on the left, in this case made of green damask and gold embroidery, made in 1635 and considered one of the oldest preserved in Andalusia. Both pieces belong to the Brotherhood of the Students of Antequera.

In front of the first canopy, the niche exhibits three costumes of the Sleeping Infant Jesus that come from the church of San Zoilo.

Inside the room we admire various liturgical vestments, such as coats, dalmatics or chasubles, highlighting the Chasuble of the Evangelists and the Black Terno de Requiem. Next to the black Terno stands out the luxurious bell ringer costume. In the central space stands the banner of the brotherhood of the Virgen de la Cabeza, from the late sixteenth century, embroidered in gold and silk on a maroon background.

In the background, the banner of the city of Antequera, granted by the infante D. Fernando, a copy made in 1534 of the original of the fifteenth century, where we recognize the symbols of Castile and Leon and the jar of lilies in the center, icon of the Order of the Terrace, from Nájera, and the purity of the Virgin.

Room XIII: Silverware

This room contains an abundant sample of the liturgical gold and silver work in Antequera. They come mostly from the numerous Antequera churches whose parishes and brotherhoods demanded the manufacture of Eucharistic and processional objects. Among this rich collection we find processional and sacred crosses, lecterns and other sacred ornaments whose chronology oscillates between the XVI and XVIII centuries.

There are also pieces made with silver from New Spain such as the trays of Mexican origin whose ornamentation is typical of the baroque of that country.

Proof of the artistic boom that arose in Antequera during the baroque period is the proliferation of workshops creating an important guild of master silversmiths and goldsmiths. The lecterns of José Ruiz, from Antequera, representing the martyrdom of Santa Eufemia, or the sacra of the master Félix de Gálvez stand out. Also distinguish the group of monstrances and pestle holders, and the magnificent oil lamp of the XVIII century, from the Collegiate Church of San Sebastian.

Room XIV: Strong Room

A real safe that treasures a valuable collection of chalices, jewels, rosaries and crowns made of gold and precious stones, many of them still in use and that were made by renowned artisans.

During the Baroque period the processional images were of great devotion among the population and this led to donations of all kinds of brothers and devotees. Proof of this are the trousseaus that have come down to us of the venerated Marian images such as the Virgen de los Remedios, del Rosario or de la Salud.

Apart from the trousseaus of the virgins, the crown with potencies of the patron saint of the city, the Señor de la Salud y de las Aguas, stands out. Although it is a modern piece, it stands out for its technical quality.

Room XV: Baroque Painting

This space houses an impressive collection of baroque paintings of religious themes typical of this artistic period. The pieces exhibited here deal with themes such as the episodes of the life of the Virgin, mostly painted by the Mexican painter Juan Correa where we can observe the looseness of his brushstroke and a freer use of color, typical of the baroque of New Spain.

We can also admire works by Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra, a disciple of Alonso Cano and one of the most important painters of Granada after Cano. We can observe some characteristic traits of his master, for example in the Virgin and Child adored by the shepherds. However, his Inmaculada, whose iconography is closer to the Sevillian painting of the time, with the hands crossed on the chest and the blue mantle almost floating in the air.

Also, Antonio Van de Pere leaves us another Inmaculada, being the centerpiece of the room showing us a delicate drawing of great chromatic richness and whose flesh tones remind us of the work of Rubens.

Antonio Arellano “el mudo” or Manuel Farfán are other artists who give us their baroque imprint in this room.

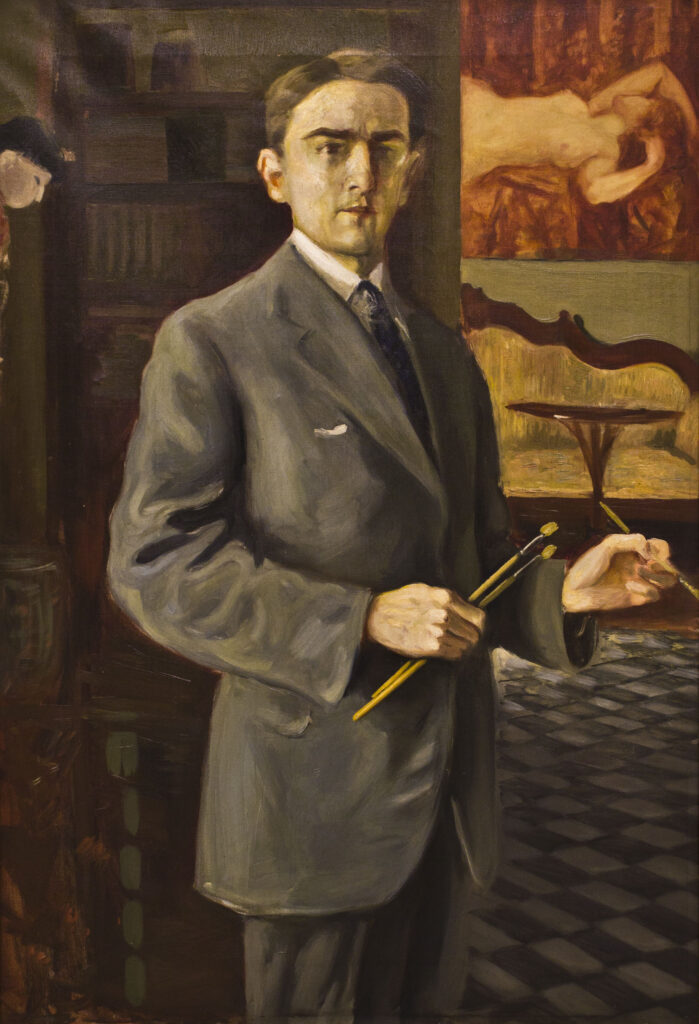

Room XVI and XVII: José María Fernández. Oil and pastel

José María Fernández Rodríguez (1881-1947) was born on Estepa Street in Antequera, into a wealthy family that owned a hardware business. He trained as a painter in Malaga with Joaquin Martinez de la Vega and traveled as a young man to different European capitals where he acquired an extraordinary artistic culture. Apart from his facet as a researcher in the fields of art and history, in which he made fundamental contributions to the knowledge of Antequera’s historical heritage, his pictorial production was very abundant and of great quality. He stood out as a magnificent draftsman, in pencil and pastel, although he also handled the brushes quite fluently in his oil paintings.

The large collection of his works preserved in the museum come from the donation made by the artist to the city of Antequera in his will. For the titles we have followed those proposed by Belén Ruiz in her studies on the author.

The tour of his work begins with a young self-portrait and two portraits of his mother and a drawing of his father.

Then hangs on the walls a series of portraits of the rest of the members of his family, in oil, such as Dolores with a Chinese doll, Portrait of Rosario with flowers, or Pepe with coat and hat.

The double Portrait of Rosario with fan on a boiler or on a blue background, as if in the first one he wanted to represent the wife with all her vitality and in the second one with the effects of tuberculosis, causes us a certain uneasiness. In all of them Fernández shows a great correction in the drawing, which he adjusts to the maximum, and a chromatic range of great richness. His loose brushstrokes and unfinished backgrounds when it comes to sketches from life for larger portraits speak of his mastery. The rooms are completed with a sample of the different themes that interested the painter throughout his life: themes of local history, Holy Week, urban planning, interior design of buildings, carnival, portraits of characters or the magnificent academic studies of which an important collection is preserved in the museum.

Room XVIII: Jesús Martínez Labrador: Sculpture and Drawing

Jesús Martínez Labrador (Antequera, 1950) is one of those sculptors for whom no material keeps secrets. With anyone he is able to recreate the perfection of the human body transformed into a symphony of movement, strength and verve. All this without renouncing to a personal and unmistakable style that has made him one of the most renowned artists of the province. Most of his sculptures represent figures and parts of the body, since he uses human anatomy as a tool to manifest spirituality. His work is influenced by the neoclassicism of sculptural geniuses such as Rodin, although impregnated with a subtle modernization that reveals a constant regeneration of his conceptual proposal and his interest in the world. The artist’s admiration for culture is manifested in his seven busts of poets of the Generation of ’27, to whom he also pays tribute with the exhibition of some fragments of their works. The poet José Antonio Muñoz Rojas wrote that Jesús Martínez Labrador sings music with his fingers, expressing cry, pain, fear or amazement.

This room gathers in this room part of his work “friends and poets”, as well as some family drawings and other pieces that show the genius of this spectacular sculptor.

Room XIX and XX: Cristóbal Toral

We ended our visit to the Museum in Rooms XIX and XX, located on the third floor of the new extension, dedicated to the painter Cristóbal Toral. This contemporary artist, born in 1940 in Torre-Alhaquirne by chance, although considered antequerano as he was even baptized in the parish of San Pedro in our city, is one of the most prominent representatives of magical hyperrealism among Spanish painters. He began his drawing studies in 1958 at the School of Arts and Crafts of Antequera, then installed in this palace of Nájera, passing the following year to the School of Fine Arts in Seville and later to the School of San Fernando in Madrid, obtaining in 1964 the National End of Career Award. Between 1968 and 1969 he received two scholarships from the Juan March Foundation to further his studies in Spain and New York, where he came into contact with the new realism of American painters. His participation in the Florence Biennial on two occasions (1973 and 1977), obtaining a gold medal, and in the Sao Paulo Biennial (1975) with the Grand Prize, made him internationally known. He has had important individual exhibitions in Madrid, New York, Buenos Aires, Mexico, Paris, Tokyo, etc.

The large format painting entitled D’apres Las Meninas (1975) stands out, a very personal version of the famous original by Velázquez, in which he reproduces in detail the hall of the old Alcázar in Madrid, but replacing the court figures with a large number of suitcases, something that will be a constant in his painting.

From his facet as a sculptor, two bronze originals are exhibited: Embalajes and La llegada, both of small format but full of symbolism related to the journey through life, so present in all the artist’s production.

Toral’s creative world, which almost from the beginning starts from reality as a plastic conception, sinks in a very personal poetics in which the presence of suitcases, weightless apples, the recreation of classics such as Velázquez and Goya, the solitude of women or the trompe l’oeil of the broken canvas, take us to the secret intimacy of the painter; of his world and his concept of space, of reality and of color.

Delgado Collection Gallery

This magnificent collection of paintings deposited in our museum completes the sample of baroque art that is preserved here, not only of local production but also foreign that came to us.

This compendium of works from the Delgado collection, which stand out for their quality and state of preservation, is a brief summary of the History of European Art in a period of time that spans from the mid-sixteenth century to the eighteenth century, and in turn a small extract of what is the taste for collecting that has its greatest boom with the European monarchies.

Among these pieces we find real artists of renown that we would currently find in art books, such as Diego Velázquez or Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, two of the great representatives of the Sevillian Baroque school, along with Francisco Herrera “the old” or Juan Valdés Leal. Alonso Cano also has a place in this exhibition as an emissary of the Granada Baroque.

There is also a small representation of French artists such as Simon Vouet or Jaques Bellange, or Italians such as Carlo Saraceni, Orazio Borgiani or Corrado Gianquinto.

The subject matter of this collection ranges from portraits, devotional content such as scenes from the life of the Virgin or Saints, and landscapes such as the latest addition by Antonio del Castillo with religious brushstrokes.

Tab content

Tab content

Tab content

Tab content

Interior room

History

History Building

Building Rooms

Rooms